First World War 1914-1918

The residents of Chenies were deeply affected by the events of both World Wars. In 1914, the murder of Franz Ferdinand led to a declaration of war that would profoundly impact villagers, despite initial expections that the war would be short. Menfolk from the area primarily joined the local Hertfordshire and Middlesex regiments, others joined regiments connected with their families, the Royal Artillery or the Royal Navy. As the war progressed some transferred to the Royal Flying Corps.

By 1917, the volunteers from Chenies and the surrounding area were bogged down with the Allied army in trenches along a broad front stretching about 470 miles from the Alps to the English Channel. Those at home knew what was happening only through newspaper reports and gossip, and would have been aware of the hospital in Chorleywood House grounds as well as those in Rickmansworth and Amersham which took on the more seriously wounded as well as men for recuperation. Rose Maliing recalls

‘One of my memories of the beginnings of the First War was seeing some of the farm horses being taken away …During the war we had concerts in the school. These were run by Mrs. Maclean who lived at Rose Cottage, now the Manse. I remember once we were dressed as geese with feathers stuck all over the costumes. The sliding doors in the school made ideal screens for the stage and the little room at the back for dressing up. Perriot Troup sang all the popular songs, one which always reminds me of them is ‘Let the great big world keep turning’. The school would be packed as everyone looked forward to such events.

(Also) during the … war the school children collected horse chestnuts and acorns for pig feed, beechnuts, to be sent to Woburn for growing into trees, and blackberries for jam making. My pick was just a half a pound for which I received one half a penny. After that my mother said I was more useful at home helping her.‘.

Despite the hardships faced by those left behind, there were some enjoable moments. Rose also rememers that ‘during 1914 a swimming bath was built in a meadow near the Chess and was greatly enjoyed by the residents of Chenies. The water was drawn from the river‘.

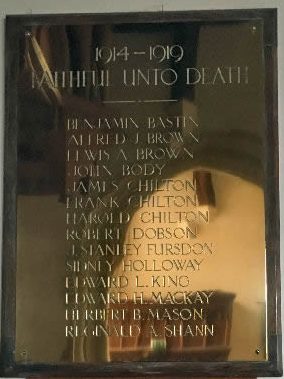

By the end of the war, in November I918, it was clear that the families of Chenies and the surrounding area had suffered horrifying loss of their menfolk. They are remembered in the plaques of St Michael’s and the Baptist Chapel.

Artilleryman Lewis Archibald Brown of the 15th Divisional Ammunition Corps, R.F.A died of pneumonia whilst in training and on the eve of his 17th birthday, on the 8th February 1915. He is buried at the Baptist Church and honoured among the roll there along with his cousin Gunner Robert Henry Dobson, of the same Ammunition Corps, who identified his body and died two years later, and his brother Gunner Alfred J Brown, of the 38th Brigade, Royal Artillery, who died on 23rd August 1918 and was buried at Godewaersvelde British Cemetery – Nord. Lewis and Alfred’s parents Ernest and Sarah lived at number 54, Chenies.

Also lost in 1918 was Lt. Reginald Arthur Shann who fell in action at Hargicourt 21st March 1918. His memorial is displayed on the north wall of the Nave at St Michael’s Church. The son of the Rector, Reginald and Elizabeth Shann, the tablet was commissioned by Adeline Marie, Duchess of Bedford, widow of the 10th Duke. The young man’s parents are buried in the churchyard.

Further losses associated with Chenies include:

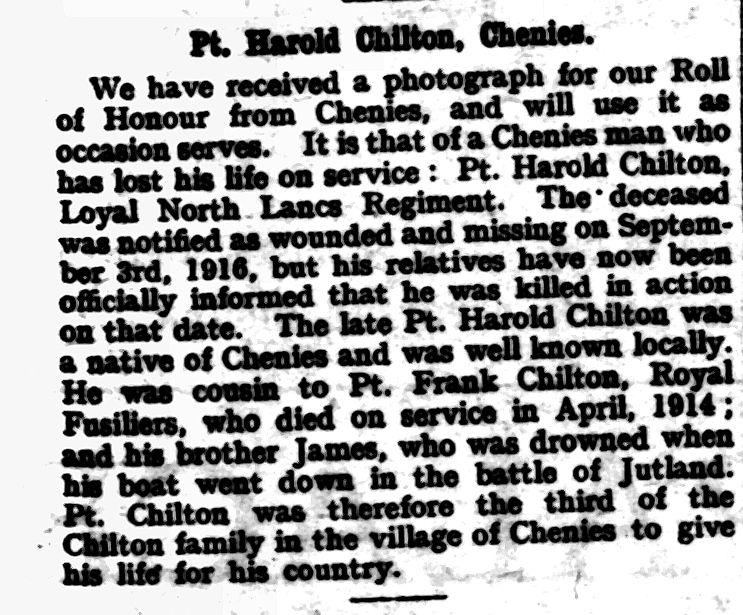

Private Frank Chilton of the 3rd BTN, Royal Fusiliers, was killed on 14th April 1915 and is buried at Tyne Cot Cemetery, West Vlaanderer (Belgium). The same family also lost Private Harold Chilton of the 9th BTN, The Royal North Lancashire Regiment, killed on 3rd September 1916 at the Somme and is buried at Thievpval Memorial, as well as Leading Stoker James Chilton of HMS Indefatigable, who was was killed on 31st May 1916 at the Battle of Jutland and is buried at the Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon. Harold resided at 52 The Plough, and his cousins Frank and James lived at 8, New Cottages, Chenies.

Captain Leslie Stafford Charles of the 60th Squadron, Royal Flying Corps of the 6th BTN, Worcestershire Regiment died of wounds 30 July 1916 as a Prisoner of War aged 21. He had been on a reconnaissance, flying in a Morane BB 5193, accompanied by Lt C Williams, on 30 July 1916, when the aircraft was last seen going down, trailing smoke, over Estrees. His parents resided at Woodside House in Chenies, and were named Mr & Mrs R Stafford Charles. Leslie is buried in Rosel Communal Cemetery in France and is memorialised by a trefoil brass altar cross at St Michael’s Chenies as follows:

GLORY OF GOD/ AND

IN EVER LOVING MEMORY OF

LESLIE STAFFORD CHARLES

CAPT WORCESTERSHIRE REGT

AT. TO RFC

WHO SERVED HIS KING AND COUNTRY

IN GALLIPOLI AND FRANCE

AND LOST HIS LIFE

FIGHTING OVER ENEMY LINES NEAR PERONNE

JULY 30TH 1916

AGED 21 YEARS

Private Albert Sidney Holloway of the 6th Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment died of his wounds on 16 November 1916 aged 31 and is buried at Serre Road Cemetery, France. Albert was a resident of Chenies Bottom.

Private Benjamin Bastin of the 17th BTN, Middlesex Regiment, died on 28th April 1917 and was buried at the Arras Memorial – Pas de Calais (France). Son of John and Jane Bastin, of Chenies.

Herbert Mason of the Royal Garrison Artillery 140th Siege Bty who died of his wounds at Richmond Military Hospital on on the 14 May 1917 aged 25. His parents John & Charlotte Mason were farm labourers at Old House Farm, Chenies.

Private John Stanley Fursdon of the Hertfordshire Regiment died on 3Ist July 1917 at Ypres and was buried at Ypres (Memorial Gate) Memorial. His parents Rev. Robert W & Elizabeth Fursdon were residents at the Manse, and his father was the minister at the Baptist Church for over 34 years.

Private John Body of the rith BTN, Middiesex Regiment, died on 14th August 1918 and was buried at Monchy British Cemetery – Pas de Calais (France). He was the son of Joseph and Sarah Body, of 69 Sheep Houses, Chenies where his family had resided for several generations.

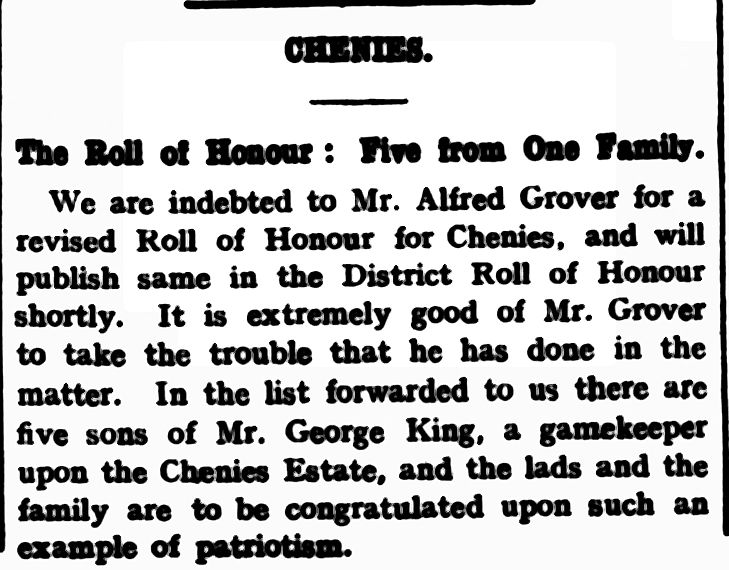

Gunner Edward King of the Royal Artillery Garrison died of pneumonia on the Ist January 1919 and was buried in the Cairo War Memorial Cemetery. His father, George King, was a gamekeeper at the Chenies Estate. At least four of his brothers also signed up to fight, and his sister was a volunteer with the Red Cross.

Edwrd H Mackay (possibly A E Mackay) is also included on the honour roll.

These terrible statistics reveal that two families lost three of their menfolk, and both the Rector of St Michael’s and the Minister at the Baptist Chapel lost their sons.

Second World War 1939-1945

The Second World War just 20 years later not only brought further lossess to a country still reeling from the First World War, it also brought greater change to villages such as Chenies, requiring those at home to play more of a part in the war effort than before.

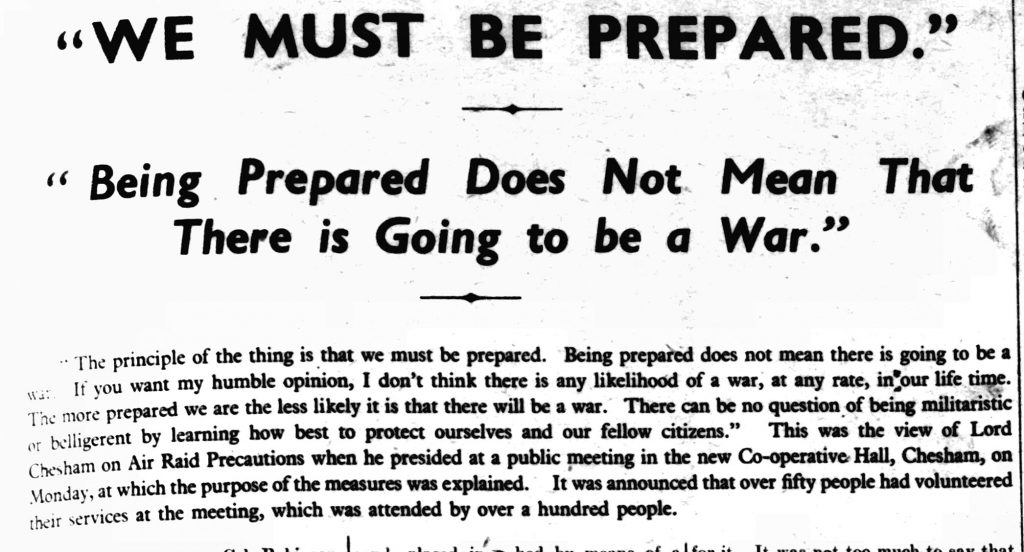

As early as 1937, preparations were being made in the area for the possibility of an upcoming war, even as many doubted it would come.

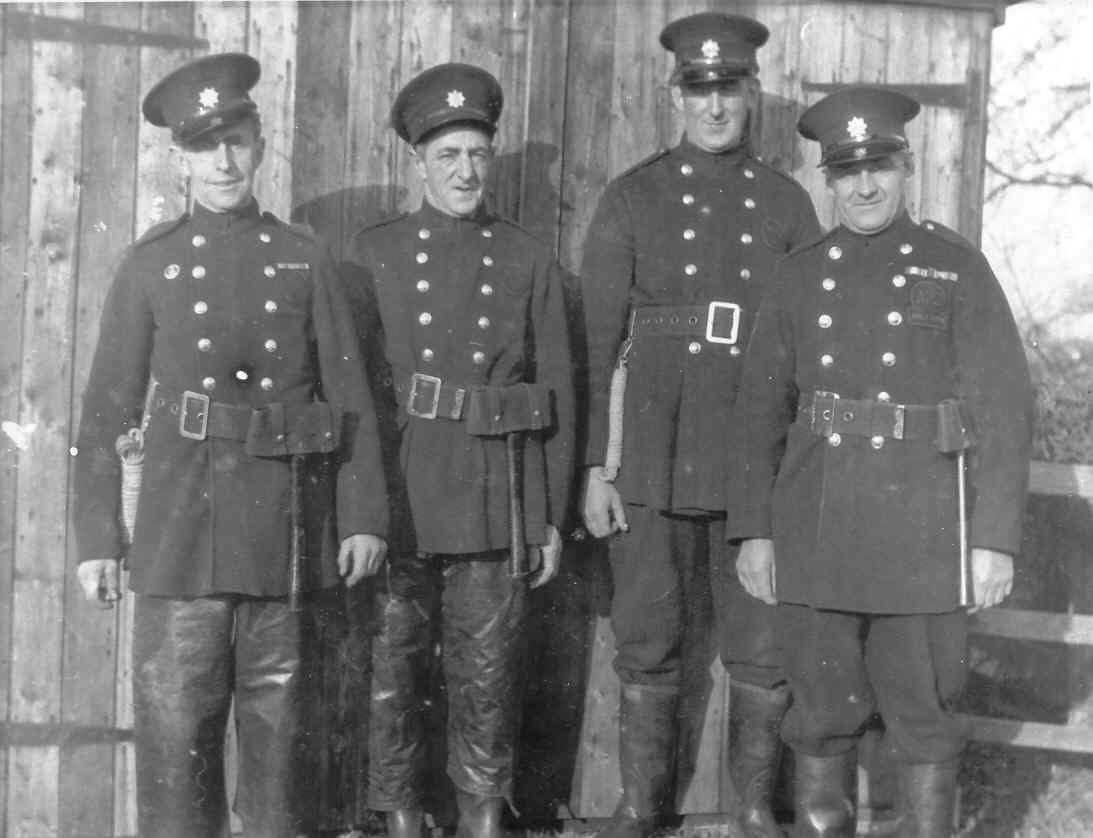

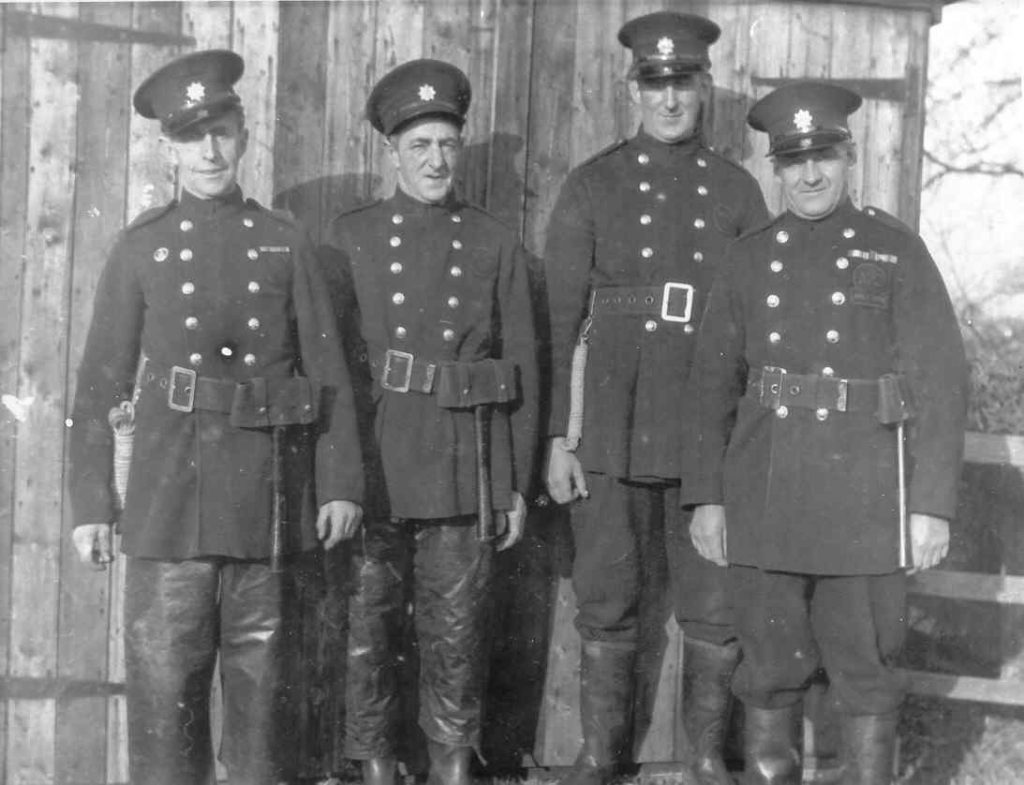

Two of the most important preperations were the establishment of the ARP (Air Raid Precautions), and the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS), which were first formed in 1938 in Great Britain as part of the Civil Defence Service. A meeting in Chenies to discuss Air Raid Precautions was held at Chenies Manor in March 1938, presided over by Rev. Fursdon, and comprehensive changes to fire fighting services were brought about in the same year, including the provision for Chenies of one stand pipe, key and bar; six lengths of hose and two branches with four men. Bu 1940, the ARF had an established unit in Chenies. These precautions brought about an increase of costs to local parishes, with costs increasing from 11s 8d for council tax in 1940 in Chenies to 12s 1d in 1941.

The ARF was particularly important given the increased risks of fire due to the bombing raids taking place across the country. The Fire Service in the area had struggled to effectively protect Chenies, and a letter dated 22 July 1914 from Adeline Duchess of Bedford was received by the council complaining of the difficulty of obtaining the services of the Brigade after a rick fire broke out on her estate.

“On July 21st last a fire broke out in a hay rick adjoining my garden wall, and close to several cottages on this estate. I gave orders at once to ring u the Rickmansworth Fire Brigade by telephone; some time elapsed, and no reply was received. After a considerable delay an intimation was conveyed from the police at Rickmansworth that the Fire Brigade telephone had been permanently disconnected, but that they could give notice of a call … As I live in the neighbourhood, and am dependent on the efficiency of the Rickmansworth Fire Brigade in case of fire, I must lodge a strong protest against the present management, which seems to me lamentable in the extreme.” Buckinghamshire Examiner, 7 August 1914.

Indeed in 1935 part of Great Green Street farm was destroyed by fire, and it was clear that these precautions were necessary. By 1941 however, the ARP and AFS units across the country were working efficiently, leading the Southern Regional Comissioner for Civil Defence to say,

“I should like to thank every man and woman of the Civil Defence Services for the magnificent work which they have done in the past year … The promptitude and eagerness with which all services have met calls … have given proof of the splendid spirit which has inspired them, while the co-operation of the three branches of Civil Defence – Police, Fire, and A.R.P.-has been admirable. We have a difficult year ahead, but with the feeling that we are on the sure road to victory I am confident that, however arduous its work may be, the Civil Arm of Defence will maintain to the full the reputation it has won for gallantry and efficiency.” Buckinghamshire Examiner, 3 January 1941.

One important role of the ARP that was implemented in Chenies was of course the blackout restrictions, a practice that was designed to protect the country from prevent crews of enemy aircraft from being able to identify their targets by sight. Outside lights were dimmed, switched off, or shielded. Essential lights such as traffic lights and vehicle headlights were fitted with slotted covers to deflect their beams downwards to the ground, and all all windows and doors were to be covered at night with suitable material such as heavy curtains, cardboard or paint, to prevent the escape of any glimmer of light which might aid enemy aircraft.

The blackout was enforced by civilian ARP wardens who would ensure that no buildings allowed the slightest peek or glow of light. Offenders were liable to stringent legal penalties, and in Chenies several individuals were fined as a result of this.

“At Beaconsfield Petty Sessions on Tuesday there were a number of lighting cases concerning Chenies Estate … Two cases raised

some argument, those against Mr. and Mrs. Cyril Mumford and Mr. Mumford being summoned in respect of an undimmed torch and Mrs. Mumford in respect of an unscreened house light … In the case of the light it was stated that a little girl aged 8 switched on the light, and in that of the torch, that it was a borrowed torch. Mrs. Mumford was fined 10/- and Mr. Mumford 5/-. Buckinghamshire Examiner 22 March 1940Mrs. Annie Elizabeth Evans, 12, Carpenters Wood-drive, Chenies Estate. was similarly summoned for an offence on October 4th.

Special-constable Simpson said light was showing from a window, caused by the wind blowing back the black-out curtain. Fined £5. Buckinghamshire Examiner, 18 October 1940.Edith Primrose Allen was summoned in respect of a light at 5, The Main Way, Chenies. The evidence of William P. Osborne, A.R.P., and Leonard Butt, special constable, showed that light was shining through a shop window, and they would have broken into the house to put it out had not somebody put in an appearance. The light was shining from a back room, and penetrated through the glass of a screen and thence through the shop window. The light came from an electric fire. Defendant’s explanation was that she left the fire on, and expected to be back before black-out. Fined €5, and costs 16/3. Buckinghamshire Examiner, 18 April 1941.”

One notable preparation the ARP made in the area in 1941 was the running of a war simulation. A note in the newspaper reminded locals that ‘War conditions will be simulated. Residents and others passing through or about the area may expect to be asked to show their Registration Cards, and those without Gas Masks may be delayed or diverted by other routes.’ Later described as the ‘Battle for Little Chalfont’, various units from the ARP, Fire Services, police, First Aid Staff and Stretcher-bearer parties took up positions and stopped members of the public to check their documents and gas masks, although regrettably many people were found to be without them.

The general scheme of the exercise was that an enemy force-represented by the 4lst Middlesex Home Guard was advancing westward from Chorley Wood, and southward from Latimer and Chenies, whilst paratroops were endeavouring to advance eastward towards Little Chalfont. Early in the operations a flight of R.A.F. machines, representing an enemy aerial force, attacked the railway station and neighbourhood. Immediately the Civil Defence Services sprang to their various duties, and the gas attack ” rattles were sounded. Everyone, including those of the civilians who had masks with them, at once donned their masks, continuing to wear them until the gas-clear bells were rung. Casualties ” were brought in to First Aid posts, and cyclist messengers, including several young boys, constantly conveyed messages between headquarters and the defending units. At noon the ‘cease fire’ was sounded, the troops returned to ‘base,’ and the several umpires made their reports to Chief Umpire Major Hutchinson. Buckinghamshire Examiner, 19th September 1941

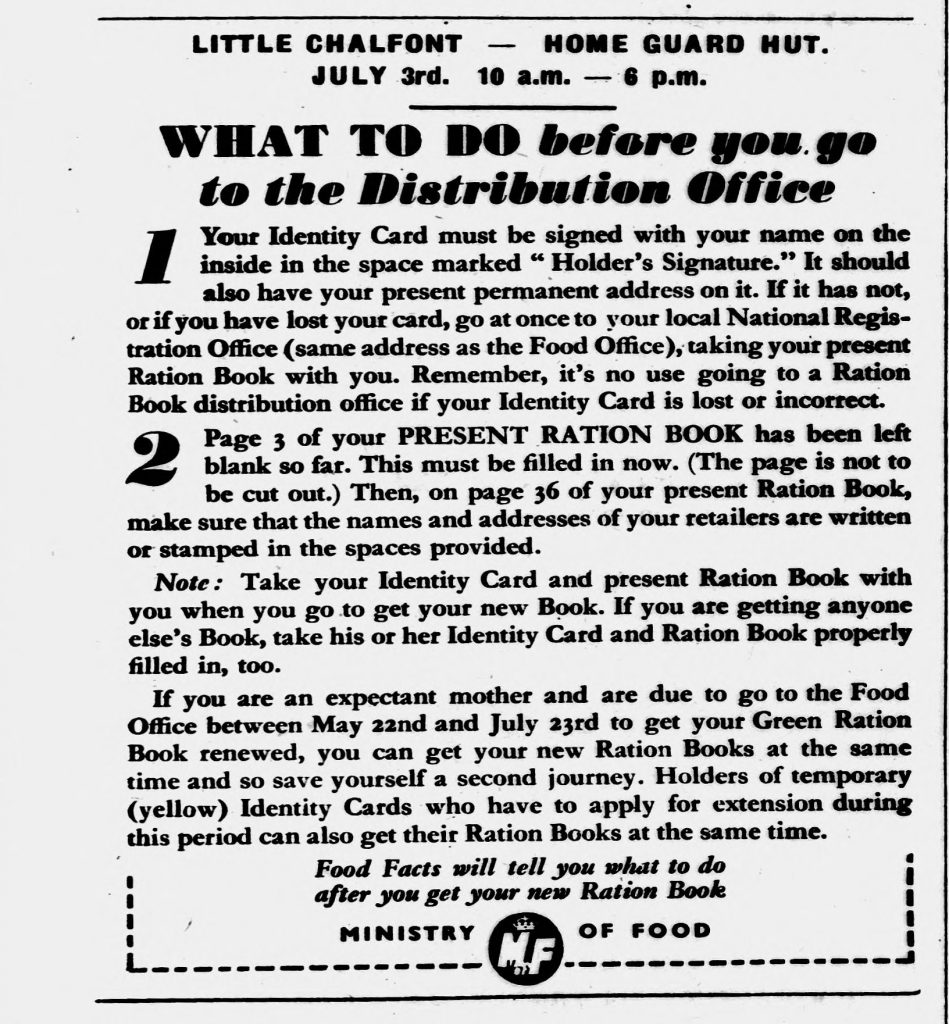

Chenies residents also had to become accustomed to food shortages and rationing. Petrol was rationed from September 1939, and was follwed by bacon, butter and sugar by January 1940. Distribution centres were set up in various locations including at Banner Rest in Chenies. Banner Rest also supplied vitamins for children between 0-2 that were provided through a government scheme, including Cod Liver Oil, Black Currant Syrup and Black Currant Puree which were considered supplementary rations.

Rationing continued right up until 1954, despite some local frustration. Housewives in nearby Gerrards Cross and Chalfont St. Peter banded together in 1946 to protest, and the Ministry of Food took out frequent adverts in the Buckinghamshire newspapers encouraging the frugal use of rations as well as making food go further.

Of course one of the biggest impacts to village life was the influx of evacuees, affecting Chenies School in particular. Emilie Life was the headteacher at that time, and she recalls:

‘Then came the war and evacuees and London (LCC) teachers. In one week, our numbers rose to 175 and the staff to six. In a room for 40 we packed 120 children, three in a desk, with two of us to instruct same. From September till May we struggled under those conditions. Perforce we had to take many combined lessons

…The evacuee children were very lovable and brought a breath of fresh air into our lives. They were, too, very amusing. One day some of the children had been teasing a red head calling him ‘ginger’ and ‘carrots’. I, trying to comfort him, said never mind Jimmy, your hair is lovely: I wish mine was that colour. “Oh Governess”, exclaimed six-year-old Joan, “You would look horrid. I like yours best silver”. Emilie Life – retirement speech (edited transcript)

Despite the strains on accommodation at the school, the arrival of evacuees had its rewards. The Chenies staff became very fond of them, and their presence made a change from the pre-war routine, though student Joe Harrison remembers that ‘we regarded them as interlopers and were rather un-sympathetic to the trauma they must have endured‘.

Several student memoirs recall their war experiences clearly.

During the war we had to practice going under the desks if the siren sounded, when in the playground we would hide in the hedges until the “All clear” sounded. Bovingdon was the home of the “Flying Fortresses” and we saw them limping home at the start of the disastrous daylight bombing campaign. On one of our walks to school we saw a Lancaster bomber which had crash landed in the 100 Acre field beside the main road to Chenies and was wedged between the trees on Stony Lane. In the later part of the war we saw a “Flying bomb” when my Dad was cycling back from church with me on the cross bar. Joe Harrison

‘I vaguely remember taking my gas-mask for a while, and one day being issued with a tin of chocolate powder which we were to take home and have hot drinks made. There was a shortage of tennis balls etc.’ – Elizabeth (Betty) Tye

‘The wail of the siren in Penge, South London, convinced our parents that their eight-year-old offspring, Pamela Houghton and Kathleen Smith, friends from the first day at school, would be safer in the country at the outbreak of the Second World War.

So it was that two ‘only children’ were ‘privately’ evacuated to ‘Loudhams’, the beautiful home in Little Chalfont of Sir Cyril & Lady Pauline Kirkpatrick, and found a place (or at least part of a deskl) in Chenies Village School. We were quite unprepared for a crowded classroom, divided by sliding wooden screens,and outside toilets of the bucket-in-bench variety. Miss Atkinson, an imposing lady with catarrhal problems, and a more diminutive Miss Ashton were the guardians of the evacuees from Barrow Hill School. Kath M Dolling

The country was a very different place by the time of the second world war. Vehicles had become more commonplace, children did not always stay in the place they were born and villages had become less insular than they were previously. As a result, not all the names recorded on the Chenies honour roll were those that lived in the village itself. Some hailed from the surrounding area, and others may have had other connections to village members that are no longer known or recorded. Remembered on the honour roll at St Michael’s and the Baptist Church are the following individuals:

Flying Officer (Pilot) Gilbert Francis Montcreiff Wright is likely the officer killed in action flying out of Hawkinge, Kent, in a Hurricane I, serial number L2120. Hit by return fire when attacking a He111 during a patrol in the Arras area, he crashed near Berneville 4 miles southwest of Arras 22 May 1940 aged 36. Gilbert was a native of Chalfont St Giles, and the son of Arthur Fitzherbert Wright and Daisy Isobel Wright; husband of Mary Doreen Wright. He is buried in Berneville Communal Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France.

Flying Officer (Pilot) Richard Adrian Hopkinson of the 57th Squadron, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve was killed in action flying a Blenheim IV, serial number R3750, out of Lossiemouth, Moray, when the aircraft was shot down by a Bf109 over North Sea during a raid on Stavanger airfield, Norway on the 9 July 1940. He was 24. His parents were Martin and Christine Hopkinson, of Bovingdon. Richard is also commemorated on Runnymede Memorial in Surrey.

Petty Officer Henry Francis Samuel Rolf was a telegraphist for H.M.S. Dunedin in the Royal Navy. He died at sea on the 24th November 1941 aged 31. Born in 1910 in High Wycombe to parents Frederick and Frances Rolf, he was also the husband of Catherine May Rolf. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial in Hampshire.

Ernest James Allen Clarkson, died at The Emergency Hospital, Amersham on the 6th May 1942 aged 26. Born in 1916 in Little Chalfont he was a Dental Surgeon and the son of Ernest T and Lilian E Clarkson.

Royal Navy Coder Alan (John) Dean served on the French Ship Mimosa (H.M.S. Avalon) in the Royal Navy and died at sea on the 9th June 1942 aged 19. Born in 1923 in Harrow he was the son of Frank and May Dean, of Little Chalfont and worked as an insurance clerk. He has no known grave but is commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial in Hampshire as well as on a plaque within St Michael’s Church which says:

IN MEMORY OF

ALAN JOHN DEAN

KILLED IN THE BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC

JUNE 9TH 1942

“WHOSE SHINING SPIRIT TRIUMPHED OVER DEATH”

Trooper William Charles Parnell was possibly of the Royal Tank Regiment, and died on the 22nd of July 1942 aged 30. Born in 1912 in South London he was a Cinema Manager, rand is commemorated on Alamein Memorial in Egypt.

Corporal Harry Fitch from the Royal Army Service Corps died as the result of an accident in the United Kingdom on the 21st January 1944. Born in Hertfordshire he was the son of Mr. and Mrs. William Fitch and the husband of Betty (nee Young) Fitch of Chenies. They were married in 1940. Harry is buried in the south-east corner of Chorleywood (Christ Church) Churchyard.

Radio Operator and Aircraftman John Lionel Crook of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (Technical Training Command) died on the 12th December 1944 aged 19. John was a native of Amersham but is buried in the St Michael’s churchyard extension. Son of John Oliver and Phyllis Mary Crook, of Amersham. In St Michaels Church is a pedestal type bookstand with plain supporting lip commemorating him.The inscription reads:

IN DEAR MEMORY OF

JOHN LIONEL CROOK

DIED ON ACTIVE SERVICE 1944

CHORISTER OF THIS CHURCH

Donald Percy Phelps was from Little Chalfont, and died on the 19th May 1944 at Royal Ear Hospital in London. His widow Phyllis Mabel Phelpsreceived his effects totalling £2124 18s. 3d.

Lieutenant Colonel Richard Douglas SUTCLIFFE, DSO, OBE, TD commanded the 69 (10th Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers). He was killed in action in the United Kingdom on the night of the 15th of April 1941 aged 50. Richard was son to Dr. Joseph Sutcliffe and Diana Frances Sutcliffe, and husband to Lily Louisa Sutcliffe, and lived in Chalfont St. Giles. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order (D.S.O.), made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.), and received aTerritorial Decoration (T.D). He is buried in Amersham Cemetery.

Graham Carington is also included on the honour roll.

content sources:

Chorleywood, Chenies, Loudwater and Heronsgate, a Social History by Ian Foster

Buckinghamshire Newspaper Articles: World War I, and World War II

Chenies Roll of Honour

contributor: Rachel Bishop

date published: 20/02/2026