The Dodds – A Village Family

John Dodd, a master paper-maker, with his wife Anne and small son George, came to Chenies in 1739. From that year and for more than a century afterwards they and their descendants became on of the most influential families in the village. They represented an example of a new middle class whose wealth was based not on land but business.

The mill situated on the River Chess and adjacent to the to the road leading to the neighbouring parish of Sarratt had been, since Stuart times, in the hands of the Farrow family, and until 1739 its function was that of grinding corn for flour. Thomas Farrow died in 1735 and his widow, Sarah, went to live in the almshouses two years later. Between 1735 and 1739 the mill was in the hands of Willaim Dyer. From that time it became the home of the Dodd family.

The reason for John Dodd’s appearance in Chenies seems to be quite clear. He came with the expressed intention of converting the mill to paper manufacture at a time when the demand for such a commodity was rapidly increasing. It also seems clear that he was a man of considerable social and economic standing before he came to Chenies for he took the mill on a 21-year lease and his acumen for business must have been sufficient to make the mill pay. It is doubtful whether he faced any difficulty in acquiring the mill because this was a period of economic change and uncertainty; a period in which the parishioners of Chenies would have been eager to see the establishment of a new industry, if not the first to be organised on a capitalistic basis.

The property itself was not extensive, there being the mill, a house and pightle, a meadow, a pond and five fields, four of which were let to small farmers in the village. It is interesting to note that the trees on this land were tied by order of the Rt Hon Francis, Earl of Bedford for the repair of both the almshouses and the Bedford Chapel, when they required it.

Two years after John Dodds arrival the mill was certainly paying its way because in that year boys from the village were being taken on as apprentices. An apprentice indenture for the year 1741 shows that Clement Weedon, a small boy of 11 years was taken on for a five-year apprenticeship. In that same year John Dodd became the overseer of the poor and in the succeeding year Churchwarden. He held appointments no less than 14 times before his death in 1775. He was certainly not a non-conformist, as no such sympathiser would have been allowed to hold a parish office. The accounts for which he was responsible during the years of his appointment ads both overseer and churchwarden reveal that he tackled all with extreme diligence. Not one mistake is recorded. This was, indeed, a true reflection of his extremely successful business.

In the early years the paper mills expansion was handicapped by the lack of trained labour for the work there. Chenies had no proper craftsmen and so Dodd had to train apprentices himself until such time as his business justified the employment of craftsmen. It seems that by 1748 his business had expanded to that extent for in that year he arranged the settlement of a Mr James Strikes, paper maker in Chenies, who, five months after his arrival, married a Chenies girl, Ann Stap. Seven years later he arranged another settlement for a Mr John Lowances, paper maker, who came from Sutton-at-Hoare, Kent, and his wife Susanna. Lowrance’s’ settlement certificate was left by a person from Sutton at the Boar and Castle, St. Giles London, to be collected by Mr Dodd. The choice of the Boar and Castle, St. Giles, and the reason for it becomes clearer when it is known that Dodd had a warehouse in the yard of that Inn. This is proven by the existence of a fire insurance policy taken out by John Dodd for his warehouse, which was obviously used for paper storage. This to some extent reveals the organisation of his business, and when this is considered, together with information given by the overseer’s accounts concerning the delivery of “rags and bags” to the mill and the printed note of “John Cattlin printer, Chesham” this organisation becomes clear. The raw materials used by Dodd for his business came mainly from local sources, but the distribution of this product was mainly to London, where, of course, the majority of printing houses were to be found.

Over the years the Dodd family prospered beyond measure, and this is clearly reflected at a family level by his son George who at the age of 23, married Sarah Davis, the daughter of John Davis, the Duke’s steward and tenant farmer of the manor. The marriage produced seven children – it should be remembered that the Dodd’s were of middle class who were not prone like their Victorian descendants to large families. Furthermore, only three of them died, and this again was quite an achievement at a time of a staggering infant mortality rate, due in part to an ignorance of childcare but in greater part to the constant danger of a smallpox epidemic.

In Parish affairs George, like his father, took an active part. Four years after his marriage and at the age of 27 he appears on the list of nominees for overseer and churchwarden. He took the office of churchwarden twenty-three times and in addition served as surveyor six times. Furthermore, the kindness of the family towards the poor is reflected in the overseer’s accounts. In those accounts numerous entries refer to the relief they gave not only to the aged, but also to children whose parents had either died or abandoned them. Indeed, it was because of the Dodd family that the unhappy life of villager Ann Harding and her sister was turned into comparative happiness. It is not surprising, therefore, that they were popular in the village. However, this happiness they gave to others was not always a true reflection upon their own family circle. Family friction arose out of the marriage between George Dodd and Sarah Davis, and cantered round the question of religion. This did not become serious but it was nevertheless an unfortunate episode which trouble an otherwise completely happy family. To find the reasons for it and the consequences it had not only on the Dodd family but also on the Davis family and others, it is necessary to trace the growth of non-conformity between 1700 and 1760 in this part of the Chilterns.

Non-conformity

Non-conformity had been a latent force in the Chilterns since the turmoil of the Wycliffe era. At that time the powerful Cheyne family had identified themselves with it and this had cost them at least one of their number. However, it was not until the turn of the seventeenth century that non-conformity became more visible and widespread. In 1741 the Newton family of Chenies acquired a licence to use their home as a Baptist meeting house, and from that time the number of people in Chenies becoming Baptists grew rapidly. By 1760 this group had grown to twenty one and the steward, Mr John Davis, had identified himself with it, although he did not become a Baptist until 1773, seven years before his death. It is known that the Rector of Chenies, who lived within the church grounds only a few yards from the manor house, was continually absent from his parish, and it is very likely that his apathy towards his fellow parishioners greatly influenced John Davis in his opinion of the Church of England. An obvious dilemma had arisen because, being the Duke’s steward, he was expected to follow the Church of England since the Duke was himself an ardent patron and especially as all his ancestors were buried in the Bedford Chapel. Furthermore, the Duke was a great friend of the Rector, Dr Jubb, and so was John Dodd. It is easy to imagine the numerous arguments both between John Davis and Dr Jubb and the Dodd family. The situation must have been intolerable for all concerned, but not once did the Duke intervene, the reason being that he lived far away at Woburn. The situation came to a climax in 1773 when John Davis resigned his position as steward and became a Baptist. The following extract from the records of the Baptist Chapel reveals quite clearly the passionate under-currents of the situations:

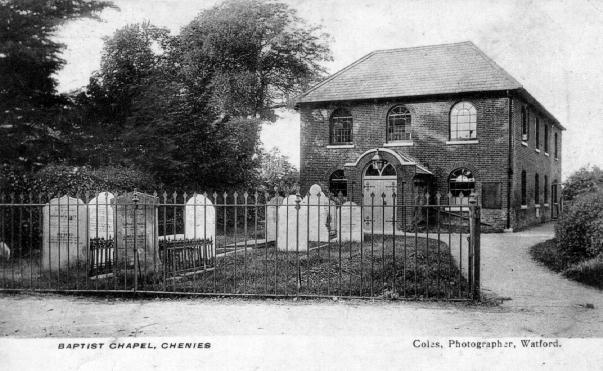

“In the year 1775, a clergyman officiated at Chenies Church whom the present rector described to me as a wolf in sheep’s clothing. It was a time of great laxity in the discipline in the Church of England, and there were a great many sporting Parsons whose lives would not bear strict investigation. This man was one of those. My great uncle Mr Davis was at the time steward to the Duke of Bedford and lived at the large house by the Church. He could not stand the goings on of the rector, so he bought two cottages and the field on which the Chapel stands, resigned his office under the Duke, helped to build and gave the land for the chapel, gave the ministers house and the land on which it stands to the cause. The whole was placed in the hands of the trustees, he retaining the cottage and garden lying between the chapel and the minister’s where he ended his days”

The Chapel was erected in 1778 upon the conditions mentioned in the above extract, (though not formally vested until 1799). Two years later John Davis died and was buried with his wife in the Chapel. The stone commemorating then is to be found under the present seating arrangement in the Chapel

content source: Dr Roy Bruton ‘A Study in Historical Anthropology’ contributor: Andy Homewood date published: 01/11/2025