Chenies Manor is located in the very eastern part of south Buckinghamshire, near the border with Hertfordshire and adjacent to St. Michael’s Church at the western edge of Chenies village. The present manor house lies on the site of the Medieval manor house, the undercroft of which is estimated to be between the 13th to the early 16th century. The surviving remains of the manor house predominantly date to the Tudor or Post-medieval period and are designated a Grade I Listed Building.

History

The Late Saxon settlement at Chenies was known as Isenhamstede, a name which may relate to its position on the river. Its first official mention however is in 1165 when it was held by Alexander de Isenhampstead who held the manor for a knight’s fee. Nothing exists of this first period of settlement except some relics of a capital and font in the present church, St. Michael’s, said to have come from an earlier church on the site.

The first of the Cheynes to own the manor was Alexander Cheyne, of the Barony of Wolverton, whose forebears came over with the Norman barons in 1066. He was presented to the church in 1232. Upon his death, which was before 1247, the manor passed to his son John (later Sir John, who became Sheriff of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire in 1278).

In 1285, with the death of Sir John Cheyne, the manor was taken by Edward I in lieu of a debt, and he spent time hunting here. At the time he also held the nearby manor of King’s Langley, and so Chenies became a ‘Chamber Manor’ – a personal rather than an official possession. The manor was valued at £11 4s 3d at the time, and John’s widow Joan was allowed to draw a pension from it.

Some documents survive referring to Edward’s ownership of the manor. The first of these is an order issued to the sheriffs of London to convey ‘two tuns’ of wine to his royal cellar at Isenhampstead. This points to the presence of a substantial manor house, probably built in stone, with substantial cellarage. A second document, cited by the antiquarian Daniel Lysons, refers to a royal visit to Chenies before Easter of 1290. The Royal Court moved to Chenies from King’s Langley on the 15th of March, and accounts survive for the hiring of carts to carry the luggage, which included a cask of ale. Some sources even suggest that he brought a camel with him, and describe the boiling and distribution of 450 eggs to the villagers on Easter Day, said to be the first recorded reference to Easter eggs in English history.

In 1296 Bartholomew Cheyne was able to present Willian de Wedon as the Rector of St Michael’s Church, though this does not conclusively prove that the manor was back in the family’s possession at this time. The manor house was eventually given back to the Cheyne family however, almost certainly by 1348, after 63 years in the crown’s possession. It was during the interim in 1321 that the name of Isenhampstead Chenies was first used, probably to distinguish it from the nearby Isenhampstead Latimer, by which time Alexander Cheyne had taken over from his father as head of the Cheyne family.

By 1350 the manor had passed to Alexander’s son Sir John Cheyne. Sir John, like his namesake, became Sheriff of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire in 1371, and a knight of the shire in 1373. He fell from grace in 1397 when he was condemned to death as a Lollard. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. His son John became the next owner.

John married in c.1400, and when his wife Agnes de Cogenhoe died he remarried in 1421 to Isabel Mortimer. He was a Member of Parliament in 1413 and 1425, and was sheriff in 1426 and 1430. John and his son Alexander conveyed the estate to one Sir Thomas Cheyne, of another branch of the family and Edward III’s shield bearer. It passed from him to his brother, Sir John Cheyne, who built part of the present Manor House after he became the owner in 1460, including the tower, two adjoining wings and a banqueting hall.

From Cheyne to Russell

John died without children in 1468, leaving the Manor to his widow, Dame Agnes. She died in c.1494-8, and in her will, she left the manor at Chenies to her niece, Anne Phelip who took possession of the manor in 1500. On the event of Anne Phelip’s death in 1510, the manor passed to her granddaughter, Ann Sapcote. Anne’s first husband, John Broughton, died in 1518, and after remarrying to Richard Jermingham she was widowed a second time in 1525. In 1526 she married a third time – to one John Russell.

John Russell and Anne chose Chenies as their main residence – it had been recently modernised and lay close to Windsor and London. Much of the surviving south wing of Chenies Manor was built during his ownership. John was a rising star at the court of King Henry VIII. By the time of his marriage to Anne, Russell had been knighted, fought in the war in France and undertaken diplomatic errands and secret missions on Henry’s behalf. According to Time Team, who visited the manor in 2004, he was one of only eight people at the time allowed to touch the King, and so it makes sense that the King would want to visit the Russells at their family seat.

Henry VIII first visited Chenies Manor in 1534. He stayed for a week, during which time the King received an agent sent by the King’s governor at Calais. He was probably at Chenies on the 6th of July when he heard of the execution of Sir Thomas More. The King no doubt took the opportunity whilst at Chenies to hunt in the two parks belonging to the manor. The royal party left Chenies on the 10th of July, accompanied by Sir John Russell.

John was created Baron Russell of Chenies, in March 1539, and in 1541 King Henry visited the manor again this time with Kathryn Howard. The house was cited in her trial for treason as being the location of one of her trysts with Thomas Culpepper. At this time the King suffered from an ulcerated leg and he was accommodated on the ground floor of the Royal Apartments., Although most likely just a fanciful story, it is said that the King’s sepulchral footsteps can sometimes still be heard on the staircase approaching the rooms in which Kathryn was alleged to “meet” Master Culpepper..

As an important figure in Henry VIII’s court, John Russell needed a home which not only befitted his status, but was also capable of housing the King and his retinue if necessary. He undertook extensive works to the complex he had acquired through marriage. Indeed, these were so substantial that by the time of Leland’s visit on one of his itineraries, probably in 1544, he remarked:

“The old house of Cheynies is so translated by my Lord Russell that little or nothing of it in a manner remaineth untranslated: and a great deal of the house has been newly set up made of brick and timber: and fair lodgings be new erected in the garden. The house is within diverse places richly painted with antique works of white and black”

The work completed by Time Team’s archeological survey in 2004 established that the present west range is likely to date to this phase of construction, and had probably been recently built at the time of Leland’s visit, and identified the present day stables as the location of the ‘lodgings … in the garden’.. The proximity of the current west range to the late Medieval undercroft suggests that it lay close to the heart of the complex, and would have been ill suited to providing peace and quiet.

John was one of the executors of Henry VIII’s will upon his death in 1547. He continued to serve the crown under Edward VI. In January of 1550 he was created Earl of Bedford.

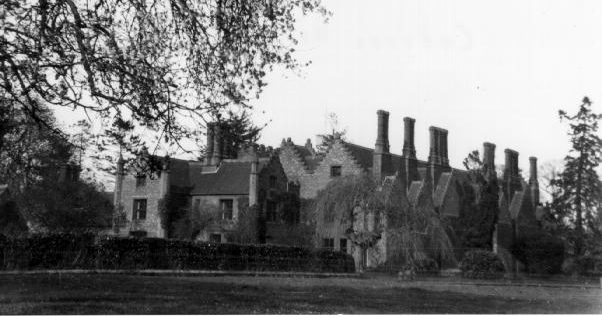

Chenies Chimneys

At this time, fireplaces were incorporated in the older buildings, as well as the additions, and nearly all the flues were furnished with ornamental chimneys, 23 of which survive. The bricks were dug from a nearby field (still known as “Claypits”) and are typical of that period, thin, and laid with blue diaper patterns at some points. The use of crow-stepped gables, expensive brick and fine fireplaces are cited as evidence of the importance and status of the building,

John Russell was succeeded as Earl of Bedford by his son Francis in 1555, and his widow, Anne, built the Bedford Chapel where he and his descendants were interred in accordance with the provisions of her late husband’s will.

Unlike his father, Francis supported the Protestant reformers, as a result of which he was imprisoned during the early years of Mary’s reign, and then spent time in exile in Italy. The accession of Elizabeth to the throne saw him return to court life.

Elizabeth I spent four weeks at Chenies in July and August of 1570. Records suggest that a surveyor visited to establish what work was required to bring it up to a suitable standard. This included the construction of new cupboards, repairs to doors, stairs and the woodwork, possibly including floorboards. William White, a glazier, was hired to install some 18 ft² of glass in the room the Queen was to occupy. The court arrived at Chenies on the 18th of July, and the Queen was accompanied by members of the Privy Council. These included the Earl of Leicester, Sir William Cecil (the Lord Chancellor), Lord Howard Effingham, the Earl of Lincoln and Sir James Crofts. Whilst at Chenies, the Queen received many visitors, including John Hawkins – her naval advisor – and a number of visiting ambassadors. The court departed Chenies on the 17th of August.

It may have been during this time that Elizabeth lost some jewellery beneath the shade of an oak tree in the grounds of the house (now named the Elizabeth Oak). In fact the records of the Royal Wardrobe detail the loss of some of her personal finery:

“Item. Lost from the face of a gown in wearing the same, at Chenies, July….One pair of small aglets, enamelled blue, parcel of 184 pairs” (transcription held by Elizabeth MacLeod Matthews).

In those early 1900’s little girls were dwarfed by the great Royal oak, under which the Queen sat in 1570 in the field by the Manor House. Unfortunately the tree is no longer alive, its bare hollowed out trunk remains as a remnant.

A young oak was presented to the Manor by the Woburn Estate as an eventual replacement. It is a scion from an acorn taken from the branch on which the last Abbot of Woburn was hanged by the commissioners of Henry VIII. The young oak was planted by the McLeod Matthews and is now a fine tree located near to where to dead ‘Elizabeth Oak’ stands.

At this time the manor was at its peak. The new south range would have been completed a few years before John Russell’s death, and the whole complex would have been impressive to behold – “three ranges of buildings grouped around a central courtyard with a substantial accommodation range facing the gardens to the north, an inner and an outer courtyard, extensive gardens containing a separate accommodation block and state apartments fit for Royalty”. (Wessex Archaeology)

Francis died of gangrene in 1585 and was succeeded by his grandson, Edward Russell at the age of 12. Francis’ debts at the time of his death exceeded all of the money available and as a result much was sold to pay them. An inventory was drawn up listing ‘nine bedrooms of consequence, three kitchens, a buttery, a ewery, a bolting house and woodsheds. The armoury for the house contained sufficient weaponry to equip 50 men. There were numerous outbuildings including two single storey ranges detached from the main buildings. These contained rooms for storage and for servants’ accommodations’. (Wessex Archeology)

After this the house went into gradual decline.

In 1601 The 3rd Earl of Bedford, Edward Russell, was involved in the Essex rebellion led by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, against Elizabeth. As a result of this he was fined £10,000 and placed under house arrest at Chenies. His wife joined him and amongst her visitors was the poet and author John Donne.

With the accession of James I to the throne in 1603 the Countess of Bedford was made Lady of the Bedchamber for Queen Anne, and had to leave for Edinburgh. This marked a change in the Russell’s fortunes and Chenies was once more occupied. However, the house was not occupied for long, and the family quit Chenies for good in 1608, eventually moving to their house in Woburn, and leaving the complex to the care of a steward. The house was occupied by a Mr Vernon, who had been an employee of the estate for some time, until his death in 1622. A female housekeeper was employed and allowed to make money from the gardens and orchards.

The 3rd Earl died in 1627, leaving no children, and the title passed to his cousin Francis Russell, the 4th Earl of Bedford who was heavily involved in the growing conflict between King and Parliament. Arrested in 1629, he was also one of the main opponents to the King at the Short Parliament held in April 1640. He died of smallpox on the 9th of May 1641.

William, the 5th Earl of Bedford, and later the 1st Duke of Bedford (1694), fought first on the side of the Parliament and then on that of the King during the Civil War between 1642-1646. Chenies Manor was garrisoned by the Parliamentarian forces during which time the Medieval undercroft may have served as a prison, as some of the graffiti inscribed on its walls is thought likely to relate to this period. A skirmish took place there in the autumn of 1642, during which the son of patriot John Hampden, a close friend of the Duke, was killed.

Interestingly the Pink Bedroom in the manor has an adjoining small closet (probably used for devotional purposes) and beneath it, reached by a (modern) trapdoor is a large hiding place (about 10ft x 4ft x 4ft high) with its own concealed ventilator. This ‘priest’s hole’ may have been used during this time. There is also a primitive long (144ft) gallery on the top storey which was used as a barracks room in the ‘Civil War. It formerly communicated to the ground by an external staircase.

William’s son, Lord William Russell, became a martyr for the Protestant cause after he was executed for his alleged involvement with the Rye House plot of 1683, a conspiracy to assassinate King Charles II and his brother the Duke of York to prevent a Catholic succession. William subsequently retired from politics, but later rose to prominence under King William and Queen Mary and was awarded the Dukedom in 1694 as compensation for the loss of his son.

The 1st Duke of Bedford died in 1700, and was succeeded by his grandson Wriothesley. He was succeeded in turn by his eldest son, another Wriothesley, in 1711. The 3rd Duke died in 1732, with no direct heirs, and the title passed to his brother, John. At this time the Church was in a poor state. The chancel roof had collapsed and the chancel was closed off.

In 1728 the west wing of the current manor house was let as a farmhouse to Mr Henry Blythe, at a rent of £23 per annum. The south wing remained largely empty and suffered from weather damage. In 1735 the family steward at Chenies reported:

“Chenies Place is a very large old house, brick built with some very large and lofty rooms, but the apartments are not very regular and of no more value than to be pulled down. There is a great deal of lead and other materials that would be very useful to repair a small box. It joins to the churchyard ” (Wessex Archaeology)

A letter surviving in the archives owned by Elizabeth MacLeod Matthews dated to 1746 describes the difficulty caused by the window tax. In it, the steward, Robert Harris, lists the number of windows in the ‘great house’:

“The uninhabited part hath about 54. In the apartment I live in 34. Mr Davies hath 28. As to the 54 they may all be stopped up except 4 or 5, which rooms we lay up the old materials. But I would hope the Parliament hath made a provision for empty houses. Out of the 34 in my apartment, I can spare 12 or 14. I shall be glad to have your advice whether close lathing will not be sufficient, without plastering, for there is some very large windows which will be considerable charge, especially if the whole empty house is to be stopped up”

The iniquity of the window tax may have played a significant part in the decision to dismantle or abandon some of the buildings within the complex.

Horace Walpole visited the house at Chenies on the 28th of September 1749. By this time much of the complex was in a sorry state of repair. He talks of the house being built around three sides of a court, falling down in places and with some of the roofs missing, although he does comment favourably on some of the stained-glass. A glazier was sent to the manor in the following year to remove much of the surviving stained glass, except for the one bearing the Russell’s arms.

In 1760 the south range was divided into five tenements for farm labourers, with new doors inserted and an extra staircase added. The steward in residence, Mr John Davis, advised that the building be pulled down, a request refused by the Duke who instead embarked upon a restoration programme inserting new window frames and rebuilding some of the west range.

Substantial repairs were also carried out to the surviving elements of the manor house in c. 1830, following occupation of an unreliable tenant. These were undertaken by the architect Edward Blore (who also worked on St James’ Palace and Buckingham Palace) for Lord Wriothesley Russell and included the restoration of the fenestrations of the house, the addition of the present front porch and door, and the encasing of the west and south elevation of the South wing in Georgian brick.

In 1840 an old Tudor building attached to the west wing of the manor was taken down and replaced with a new structure. Two bay windows were added to the west of the house in 1860 and the brewhouse was demolished.

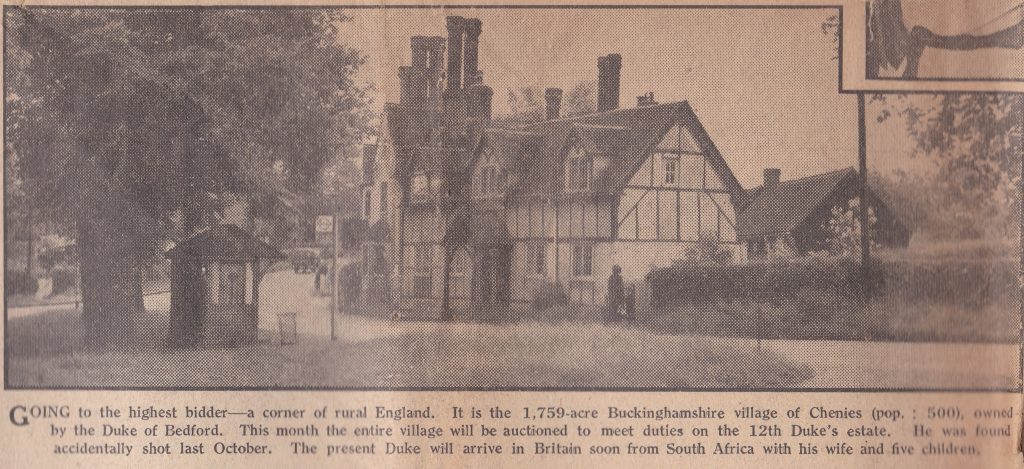

The 12th Duke of Bedford’s estate was split up and sold for auction in 1954 after he was accidentally shot in a hunting accident in October 1953. The scale of the death duties, amounting to £4.5 million, owed by the Bedfords at that time necessitated the sale of the Manor and the houses owned by the Bedfords in Chenies village. The house was bought by Alistair and Elizabeth MacLeod Matthews in the late 1950’s. It was nearly derelict and the gardens overgrown. Since that time it has been lovingly restored and has passed to the next generation, Mr Charles MacLeod Matthews and his wife Boo. Detailed pictures and much more can be viewed on their website: www.cheniesmanorhouse.co.uk

The information in this article is as accurate as possible according to current research as of February 2026, but may be subject to change in the future as new information comes to light.

content sources:

Wessex archaeology (January 2005). “Chenies Manor, Chenies, Buckinghamshire: An Archaeological Excavation of a Tudor Manor House and an Assessment of the Results” (PDF).

Chorleywood Field Studies Centre, Dr Roy Bruton ‘A Study in Historical Anthropology’.

Pamphlet ‘Chenies Manor House, Historical and Architectural Description‘ (revised Aug. 1978), and various other leaflets (sources unknown).

Chenies Manor Guides Doug King and Anne Hamilton, in consulttion with Charles and Boo MacLeod

contributor: Andy Homewood, Rachel Bishop, Doug King, Anne Hamilton

date published: 10/02/2026